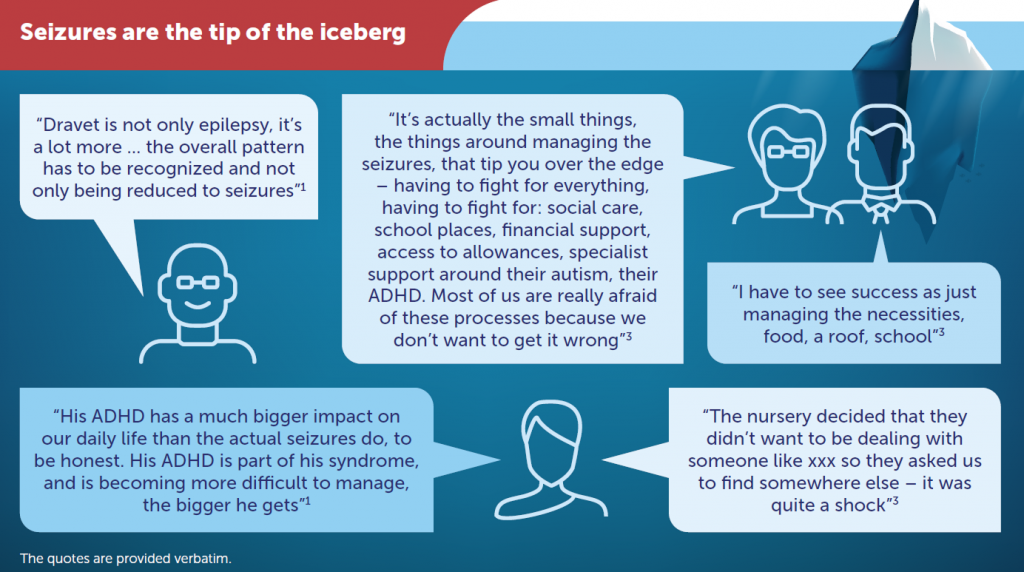

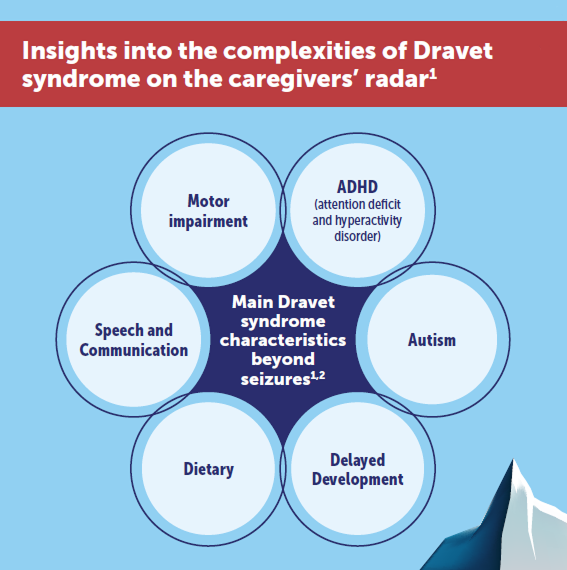

- A lifelong condition with significant impact on quality of life (QoL) for patients and families3-5

- Usually starts in childhood

- Can affect development

- Doesn’t respond well to treatment (treatment-resistant)

- There is no cure for Dravet syndrome⁶

- Generalised tonic-clonic – Begins with stiffness in the arms and legs, followed by jerky movements in the arms, legs, and head with a loss of consciousness

- Myoclonic – Involuntary, brief, jerk-like movements that cause a sudden muscle contraction

- Hemiclonic – Affects only one side of the body

- Tonic – Stiffness in the arms and legs

- Clonic – Jerky movements in the arms, legs, and head

- Tonic-atonic – Muscles in the body become stiff and then relax

- Focal with clearly observable motor signs – Affects a limited area of the brain and the affected person remains conscious

- Febrile stage (infancy):26 High probability of diagnosis within the first year, characterised by long-lasting seizures related to fever, often requiring emergency treatment.

- Worsening stage (1-5 years):26, 27 Motor seizures become more common, triggered by environmental factors, other seizure types may appear, such as myoclonic seizures or absences. Children may show lack of coordination, loss of muscle tone, and a decline in dexterity.

- Stabilisation stage (around 10 years):26, 28 Seizures become shorter, less frequent, occurring during sleep, tonic seizures may occur, with milder forms having one episode per year. Patients develop a crouching gait, often leaning on others or using a wheelchair. Cognitive impairment is often present.

- Adulthood:26, 28, 29: Seizures persist, mainly during sleep, with generalised tonic-clonic seizures. Progressive worsening in adulthood includes movement disorders, tremors, and symptoms akin to Parkinson’s disease. Other seizure types may diminish, but adults may face additional health problems due to Dravet syndrome. About a quarter of patients may also experience loss of bone density with an increased risk of fractures

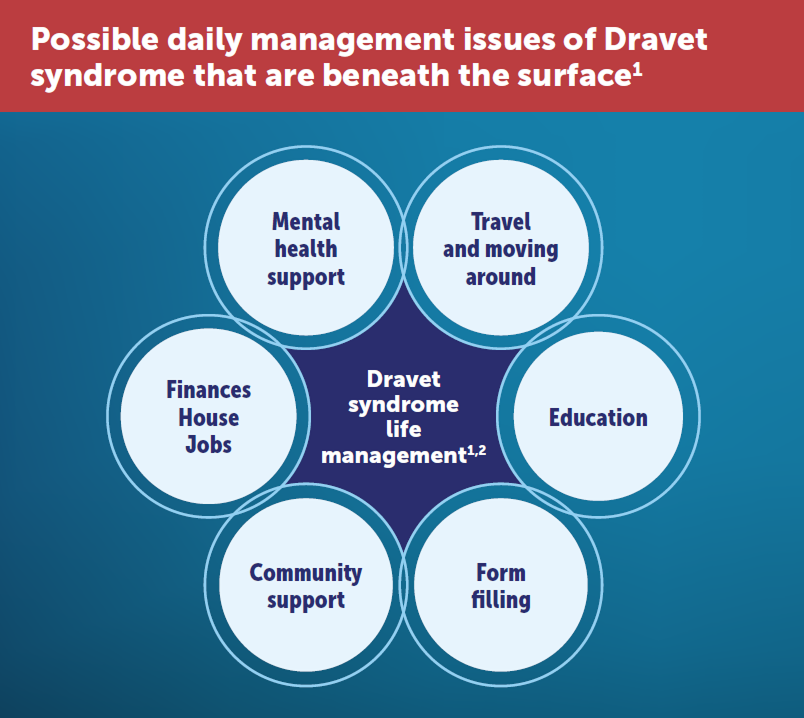

- Gait disturbance – Can impact patient independence

- Sleep – Sleep difficulties worsen seizures, more seizures lead to less sleep, creating a cycle

- Toilet training – Late to learn, sometimes incontinent

- Feeding – Feeding difficulties

- School – Missed school days, require additional support

- Antiseizure medications

- Ketogenic diet16, 35, 36

- Trigger management37

- Vagus nerve stimulation (pacemaker-like device that sends electrical impulses to the vagus nerve in the neck)38

- 66% of caregivers experience depression due to the devastating nature of Dravet syndrome29

- 35% of adult siblings report a history of treatment for clinical depression44

- 58% of siblings aged 9-12 reported feeling worried or scared when their sibling has a seizure44

- 74% of caregivers report concerns about the emotional impact on siblings of children with Dravet syndrome29

- 79% of siblings aged 9-12 feared that their siblings might die44

- 81% stopped working because of their caregiving responsibilities4

References:

1. Campbell JD, Whittington MD, Kim CH, et al. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;80:152–6. 2. Cardenal-Muñoz E, Auvin S, Villanueva V, et al. Epilepsia Open. 2022;7(1):11–26. 3. Zuberi SM, Wirrell E, Yozawitz E, et al. Epilepsia. 2022;63(6):1349–97. 4. Lagae L, Irwin J, Gibson E, et al. Seizure. 2019;65:72– 9. 5. Wirrell EC, Hood V, Knupp KG, et al. Epilepsia. 2022;63(7):1761–77. 6. Dravet Syndrome UK. Treatments and Outcomes. www.dravet.org.uk/ about-dravet-syndrome/treatments-and-outcomes/. Accessed July 2024. 7. Wu YW, Sullivan J, McDaniel SS, et al. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):e1310–5. 8. Brunklaus A, Ellis R, Reavey E, et al. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 8):2329–36. 9. Darra F, Battaglia D, Dravet C, et al. Epilepsia. 2019;60(S3):S49–S58. 10. Cetica V, Chiari S, Mei D, et al. Neurology. 2017;88(11):1037–44. 11. Marini C, Scheffer IE, Nabbout R, et al. Epilepsia. 2011;52(S2):24–9. 12. Claes L, Del-Favero J, Ceulemans B, et al. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68(6):1327–32. 13. Nabbout R, Gennaro E, Dalla Bernardina B, et al. Neurology. 2003;60(12):1961–7. 14. Wallace RH, Hodgson BL, Grinton BE, et al. Neurology. 2003;61(6):765–9. 15. Fujiwara T, Sugawara T, Mazaki-Miyazaki E, et al. Brain. 2003;126 (Pt 3):531–46. 16. Figueiredo R, Rocha R, Freitas Baptista C, et al. Birth Growth MJ. 2021;30(4):213–8. 17. Gil-Nagel A, Sanchez-Carpintero R, San Antonio V, et al. Rev Neurol. 2019;68(2):75–81. 18. Cross JH, Galer BS, Gil-Nagel A, et al. Seizure. 2021;93:154–9. 19. Sullivan J, Benítez A, Roth J, et al. Epilepsia. 2024;65(5):1240–63. 20. Wirrell EC, Laux L, Donner E, et al. Pediatr Neurol. 2017;68:18–34.e3. 21. Epilepsy Society. Seizures An introduction to epileptic seizures. https://epilepsysociety.org.uk/sites/default/files/2023-12/SeizuresNovember2023_3.pdf. Updated Nov 2023. Accessed July 2024. 22. Edwards JC. CNS Spectr. 2001;6(9):750–5. 23. Fisher RS, Cross HJ, D’Souza C, et al. Epilepsia. 2017;58(4):531–42. 24. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Types of Seizures. www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/epilepsy/types-of-seizures. Accessed July 2024. 25. Medlink®Neurology. Hemiclonic seizures. www.medlink.com/articles/hemiclonic-seizures. Updated Jan 2024. Accessed July 2024. 26. Gataullina S, Dulac O. Seizure. 2017;44:58–64. 27. Miller IO, Sotero de Menezes MA. SCN1A Seizure Disorders. 2007. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2024. Accessed July 2024. 28. Wyers L, Van de Walle P, Hoornweg A, et al. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2019;23(3):357–67. 29. Villas N, Meskis MA, Goodliffe S. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;74:81–6. 30. Jensen MP, Liljenquist KS, Bocell F, et al. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;74:135–43. 31. Skluzacek JV, Watts KP, Parsy O, et al. Epilepsia. 2011;52(S2):95–101. 32. Kalume F. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2013;189(2):324–8. 33. Harden C, Tomson T, Gloss D, et al. Neurology. 2017;88(17):1674–80. 34. Dravet Syndrome UK. DSUK Family Guide. www.dravet.org.uk/dsuk-family-guide/. Updated Jan 2024. Accessed July 2024. 35. Gorria Redondo N, Angulo García ML, Montesclaros Hortigüela Saeta M, et al. An Pediatr (Barc). 2016;84(6):341–3. 36. Garcia-Peñas JJ. Rev Neurol. 2018;66(S01):S71–5. 37. UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital. Dravet syndrome. www.ucsfbenioffchildrens.org/conditions/dravet_syndrome/treatment.html. Updated Feb 2024. Accessed July 2024. 38. González HFJ, Yengo-Kahn A, Englot DJ. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2019;30(2):219–30. 39. Dravet C. Epilepsia. 2011;52(S2):3–9. 40. Wylie T, Sandhu DS, Murr NI. Status Epilepticus. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan. Accessed July 2024. 41. Lagae L, Brambilla I, Mingorance A, et al. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018;60(1):63–72. 42. Brunklaus A, Dorris L, Zuberi SM. Epilepsia. 2011;52(8):1476–82. 43. Whittington MD, Knupp KG, Vanderveen G, et al. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;80:109–13. 44. Bailey LD, Schwartz L, Dixon- Salazar T, et al. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;112:107377.

This information has been produced by UCB

FIN0063