LGS: a rare and severe form of epilepsy that usually starts in childhood¹. Nobody is born with LGS. It may develop over time from childhood seizures that remain uncontrolled by treatments2.

- LGS affects an estimated: 2 in 10,000 people in the European Union3.

- LGS is more common in males than females4, 5.

- Known causes (in approximately 65% to 75% of patients with LGS)4, 6, 7: underlying structural brain abnormality (from head trauma, birth injury from childbirth complications, tuberous sclerosis, infection such as encephalitis and meningitis, brain malformations, or tumours), genetic disorders, metabolic causes

- Diagnostics8-10: Clinical history (seizure types and intellectual impairment), Clinical evaluation (e.g., EEG and neuroimaging studies such as MRI, CT or SPECT), Genetic testing, Lab testing.

- Key characteristics: Seizure onset in childhood, More than one type of seizure, Abnormal brain waves on the electroencephalogram (EEG), Developmental delay* *Developmental delay is not required to make the LGS diagnosis and 30% of children are typically developing at diagnosis12.

The most common seizure types are:2, 11, 16-18

- Tonic – Stiffness in the arms and legs

- Atonic seizures – Sudden relaxing of muscles, usually causing the person to fall

- Generalised tonic-clonic – Begins with stiffness in the arms and legs, followed by jerky movements in the arms, legs, and head with a loss of consciousness

- Atypical absence – Brief altered consciousness with prolonged staring and subtle movements

- Non-convulsive status epilepticus – Prolonged seizure activity without convulsions

- Myoclonic – Involuntary, brief, jerk-like movements that cause a sudden muscle contraction

- Focal impaired awareness – Affects a limited area of the brain and the affected person remains conscious. These may remain focal or evolve to bilateral tonic-clonic seizures

- Epileptic spasm – Brief events of arm, leg, head flexion or extension

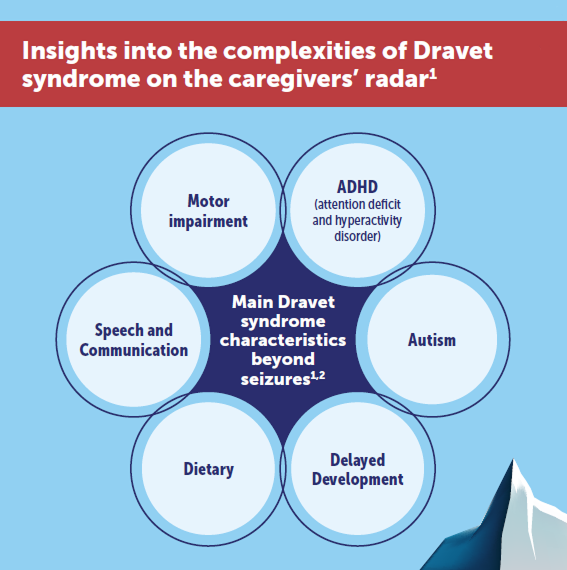

Other features

Other features in LGS include:¹¹ Impact on sleep, Cognitive delay and behavioural issues, Motor and mobility difficulties.

LGS…

- Has a significant impact on quality of life (QoL) for both patients and their families19

- Patients often suffer from lifelong motor, cognitive, and behavioural abnormalities9, 19

- Poor long-term outcomes for patients9

- Complete seizure freedom is unusual9

- Has an increased risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) due to uncontrolled seizures20-22

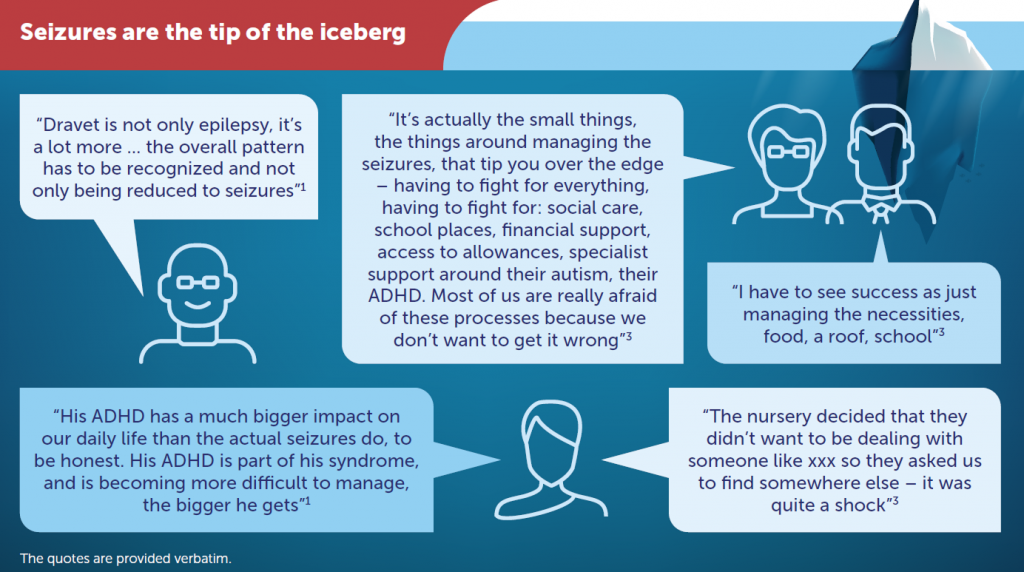

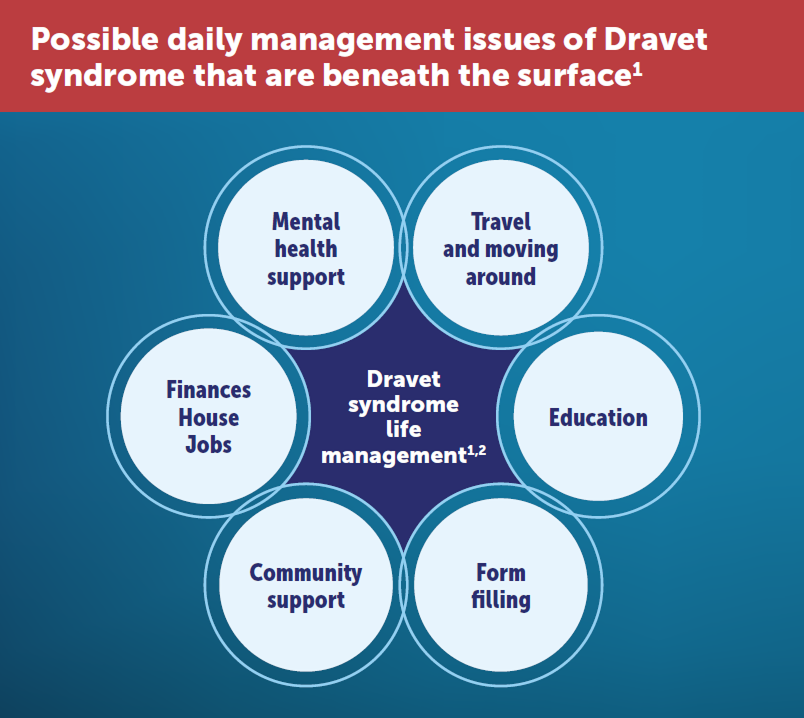

Key challenges for caregivers:23-24

- Emotional burden and isolation

- Family dynamics

- Financial strain

- Lack of understanding of LGS

- Transitioning from paediatric to adult care

- Fear, anxiety, stress, and depression

- Logistics around providing care

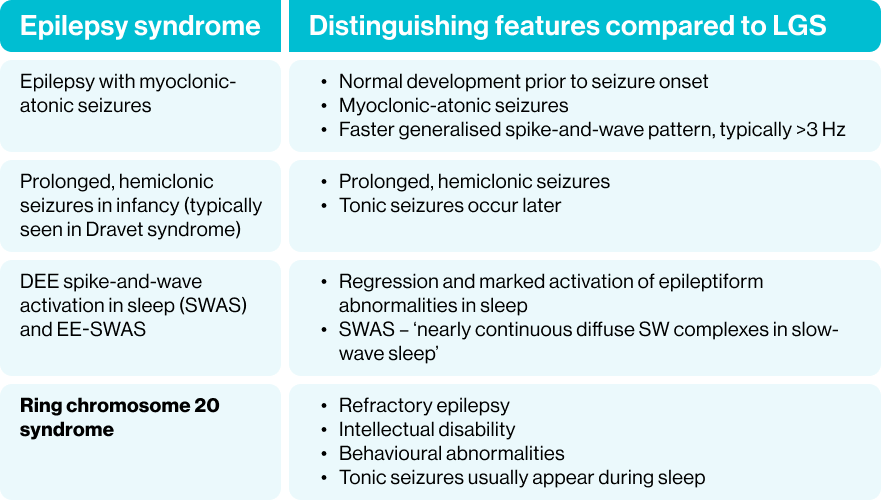

LGS and other epilepsy syndromes share clinical and imaging features11, 25

Abbreviations: LGS, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome; EEG, Electroencephalogram; MRI, Magnetic resonance imaging; CT, Computed tomography; SPECT, Single-photon emission computed tomography; QoL, Quality of life; SUDEP, Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy; DEE, Developmental and epileptic encephalopathy; SWAS, Spike-wave activation in sleep; EE-SWAS, Epileptic encephalopathy with spike-wave activation in sleep; SW, Spike-wave.

References:

Strzelczyk A, Zuberi SM, Striano P, et al. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2023;18(1):42. 2. Ajinkya S, Wirrell E. What is Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome? LGS Foundation.

www.lgsfoundation.org/about-lgs-2/what-is-lennox-gastaut-syndrome/. Updated March 2024. Accessed June 2024. 3. European Medicine Agency

EU/3/17/1855. www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/orphan-designations/eu3171855. Accessed June 2024. 4. Asadi-Pooya AA. Neurol

Sci. 2018;39(3):403–14. 5. Khan S, Al Baradie R. Epilepsy Res Treat. 2012;2012:403592. 6. Al-Banji MH, Zahr DK, Jan MM. Neurosciences (Riyadh).

2015;20(3):207–12. 7. Amrutkar CV, Riel-Romero RM. Lennox Gastaut Syndrome. StatPearls. 2023. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30422560/.

Accessed June 2024. 8. Arzimanoglou A, French J, Blume WT, et al. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(1):82–93. 9. Camfield PR. Epilepsia. 2011;52(S5):3–9.

10. Jahngir MU, Ahmad MQ, Jahangir M. Cureus. 2018;10(8):e3134. 11. Specchio N, Wirrell EC, Scheffer IE, et al. Epilepsia. 2022;63(6):1398–442.

12. LGS Foundation Fact Sheet. LGS Foundation. www.lgsfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Updated-MAY-2024.png. Updated May

2024. Accessed June 2024. 13. Trevathan E, Murphy CC, Yeargin-Allsopp M. Epilepsia. 1997;38(12):1283–8. 14. Lennox Gastaut Syndrome The

Natural History Project. LGS Foundation. www.lgsfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/LGS-Caregiver-Driven-Natural-History-Survey.pdf.

Updated August 2021. Accessed June 2024. 15. Bourgeois BF, Douglass LM, Sankar R. Epilepsia. 2014;55(S4):4–9. 16. Epilepsy Foundation. Tonic-

Clonic Seizures. www.epilepsy.com/what-is-epilepsy/seizure-types/tonic-clonic-seizures. Updated June 2022. Accessed June 2024. 17. Epilepsy

Foundation. Status Epilepticus. www.epilepsy.com/complications-risks/emergencies/status-epilepticus#Nonconvulsive-Status-Epilepticus. Updated

May 2023. Accessed June 2024. 18. Epilepsy Foundation. Epileptic or Infantile Spasms. www.epilepsy.com/what-is-epilepsy/seizure-types/epilepticor-

infantile-spasms. Accessed June 2024. 19. Cross HJ, Auvin S, Falip M, et al. Front Neurol. 2017;8:505. 20. Berg AT, Nickels K, Wirrell EC, et

al. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):124–31. 21. Resnick T, Sheth RD. J Child Neurol. 2017;32(11):947–55. 22. Autry AR, Trevathan E, Van Naarden Braun K, et al. J Child Neurol. 2010;25(4):441–7. 23. Gibson PA. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2014;7:441–8. 24. Gallop K, Wild D, Veridan L, et al. Seizure. 2010;19(1): 23–30. 25. Wirrell EC, Nabbout R, Scheffer IE, et al. Epilepsia. 2022;63(6):1333–48.

This information has been produced by UCB

FIN0064